Recently I’ve had time to catch up and reflect on a few games that all touch on aspects of mental illness. I tend not to write personal blog posts, but I want to share some of my thoughts on these games as they made me think about interactive storytelling and mental illness, at a time where I’m currently reflecting on a lot on my own life. Although I’m not going out of my way to spoil the plots of these games, I’m going to assume that by reading this post you have either played them or don’t care about spoilers. The games I talk about are Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, Spec Ops: The Line, and Firewatch.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

The game that provoked this blog post was Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, an independent triple-A title by UK based Ninja Theory, released for PlayStation 4 and Microsoft Windows in 2017, and then for Xbox One earlier this year. It’s a third person action adventure game, with melee combat and puzzles and making up the core game play. Initially I’d heard about the title and been interested in the story, but the death mechanic left me thinking it would be too difficult for me to want to tackle at the time, and I put it on the back burner. I usually get to games late these days as I’m busy with work, this blog, and my personal life. I occasionally take a chance on a game, and in this case I’m glad I did. This isn’t intended to be a review, but as it’s still relatively new I’ll say this: I like Hell blade a lot. It’s a technically impressive game. The world and design of the characters are so detailed and high fidelity. There’s fantastic audio design, great music, and excellent performance capture and voice acting from the entire cast, which I think is it’s stand out achievement. For those expecting a deep and complex melee combat system, I don’t think you’ll find it here, that’s not the focus here. The combat has a narrative function and I found the mechanics challenging enough for me, although generally I don’t seek out melee combat games. The puzzles are well done, and they too serve a narrative purpose, although most are perhaps a little basic. The game is more than the sum of its parts, the entire experience is a must.

What drew me into the game from the outset was the slow introduction to the main character, Senua and her world. Senua struggles with psychosis in a time where mental illness is believed to be a curse. During the introduction one of the voices, the narrator welcomes you to the game and introduces you to Senua’s and the world. The other voices in her head then make their presence known and are present for the entire game. I felt like I was joining the game as one of the voices in Senu’s mind, I immediately felt invested in her and intrigued in what lay ahead. The narrator is one of the kinder voices that are present throughout the game, and one which grounded me. The other non-stop voices range from barely audible whispers to disconcerting, rages at times. Even when the voices are at a normal speaking level, they are an unsettling and confusing mix of instructions, mocking insults, questions, warnings, incorrect information, platitudes, doubts of your abilities, and compliments. This is one of parts of the game that really hit close to home for me. There are several game play sequences that were downright unsettling to the core and others that were terrifying on a deeply personal level. I played through Hellblade in a single play through and by the end I was emotionally drained and mentally exhausted, and I consider this to be the point. Games require interaction from the player to work and that’s what makes them different from other media. You go through the same experiences as the character, being directly involved in the events that occur, and you come out the other side changed. The game isn’t real, but you are, and your emotions and thoughts are. One of the reasons Hellblade works is that the story is so personal. You are not the chosen one who’s going to save the planet/galaxy/universe, you’re on a personal journey with Senua trying to do what you believe you must for a loved one, and that’s an aspect that’s true of the other games featured in this post. After completing Hellblade, I was reminded of another game I’d played years previously which left me feeling in a similar way.

Spec Ops: The Line

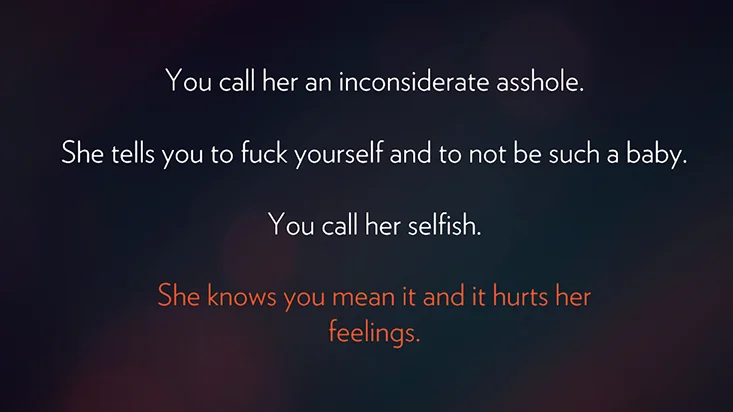

Spec Ops: The Line is a modern military third person cover shooter released in 2012 by Yager Development, and it’s not at all like Hellblade in game play or execution but does deal with mental illness although in a more bombastic and cinematic way. Whereas Ninja Theory worked closely with neuroscientists, mental health specialists, and people with psychosis, Yager Development took inspiration from Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now. Not to diminish their work at all, but I feel it’s important to make the point that both developers were working towards different goals in different eras of our culture and game development. Spec Ops: The Line’s main character is Captain Martin Walker. You’re introduced to Walker and his team Adams and Lugo in a helicopter-based turret sequence which ends quickly due to sand storms causing the helicopter to crash. There’s then a fade to white and the game starts at the beginning of the story, eventually catching up to the helicopter crash and then moving to the finale. As the story progresses, Walker’s mental health deteriorates and by the last chapter, both Walker and the player are left wondering exactly what it is going on. One of the goals of the developer’s is to make the player question their actions and expectations of war themed video games, at the same time as Walker does in the story. The loading screens for most of the game offer helpful game play hints as expected, but as the player progresses the hints become more critical of Walker’s and the player’s actions, asking you “Do feel like a hero yet?” When reaching the point in the story where you catch up to the opening helicopter sequence, Walker mentions already having done this and expresses confusion before disregarding it. There’s lots of hidden subtleties like this that open the door for more interpretations of the story, and the time and care taken by the developers to put in these subtleties should be praised. The fact they put these almost invisible additions in bolsters the fact that Spec Ops: The Line intentionally wanted to transcend the typical modern military shooter in 2012, and it still holds up today.

It’s worth highlighting the choices that occur throughout the game. They aren’t telegraphed by using button prompts and the choices aren’t spelled out, so they’re easy to miss. The player must act using the game play mechanics, not simply press a button and trigger an animation and a line of dialogue. It really makes you feel and responsible for what you do or fail to do. The biggest choice is the catalyst for the bulk of the plot, where you are given the option of using white phosphorous against the enemy. In truth it isn’t even a choice as you are facing an overwhelming force and even if you try to fight, you’ll be killed, so you are forced to do what the game and plot requires you to do in this instance. However, the characters discuss this, “There’s always a choice.” Lugo says, and Walker responds with “No, there’s really not.” I’ll speak for myself; I’m so used to these types of games, I just did what I felt was expected of me and used the white prosperous, but of course that’s the point. So, does Walker, he doesn’t see another choice, and so you are he make the choice, and do the deed. The section afterwards where, instead of moving on to the next combat section or self-congratulatory cut scene, you walk through the area you just bombarded and see the death and destruction you caused is truly chilling, and here begins Walker’s mental breakdown and the root cause of his dissociative disorder.

Much like Hellblade the player is with Walker throughout the game, you see events through his eyes and are introduced to him during the game’s open chapters. The mission that Walker and team are on is only initially personal as the team they are checking in on is commanded by Walker’s old commander from a previous conflict, but it escalates to Walker mentally torturing himself for his terrible actions. Spec Ops: The Line’s initially hidden goal is the exploration of a mental state, PTSD, and player expectations.

Firewatch

Firewatch is a first-person adventure game developed by Campo Santo and released in 2016. I got around to playing it in the Christmas-New Year lull of 2016. You take the role as Henry, who takes a job as a fire lookout in Wyoming. The game is very narrative driven and focuses on exploration of the area surrounding the lookout tower and Henry’s relationship with his supervisor Delilah, the only other person who he can speak to. The player can choose conversation options or choose not to speak at all. As the game progresses several strange events take place, more paths are opened for the player to explore and mysteries develop.

The reason that Firewatch stood out to me is because of the set up for Henry and why he’s taken the job in the first place. When you start the game, you are introduced via text to Henry and a woman who he meets. They get married and have a happy life together but over time his wife develops early-onset dementia and eventually Henry runs away and takes the fire lookup job. During your time with Henry, thoughts and worries of his wife and her condition disappear into the background as you get to know Delilah, perform mundane tasks and encounter mysteries. Although I don’t specifically want to spoil the ending or specific plots points, I am going to talk about the ending. By the end of the game, what seemed like a conspiracy against Henry and Delilah, turned out to be something much simpler and personal to Delilah. Although Henry didn’t hurt anyone or do anything intentionally to hurt anyone, his actions do end up making Delilah aware of a mistake she made that cost a child their life. At the finale, Henry and Delilah leave the forest and say their goodbyes. After the entire experience, Henry is still left with his pain or running aware from his wife. I live in a rural area and grew up in an even more rural area and the forest in Firewatch reminded me of my childhood, which is possibly one reason why it struck a chord with me. Although Henry isn’t the one dealing with mental illness in this game and it’s not really a focus, it made me consider the friends, family, and loved ones of people who have mental illnesses and how we deal with the effect of our actions, or inaction and our mistakes, and ultimately what we leave behind us after we’re gone.

If you have any questions or comments, please leave them below. Thank you.

-Mike